20th Century, Suite, Works

This work began as a film score. In 1934 Prokofiev was commissioned to compose a score for Lieutenant Kijé (in Russian, Parootchik Kizhe), a movie satirizing the military and bureaucracy in Czarist Russia.

The plot is based on a mythical tale that hinges on a spelling error. In the film, a clerk misspells a phrase while copying out military orders: the Russian phrase “parootchiki, zheh” (“the lieutenants, however…”) becomes “Parootchik Kizheh (“Lieutenant Kizheh”). The Czar reads the orders and thinks there is a “Lieutenant Kijé” in his guard company!

Not daring to tell the Czar about the copying mistake, the Czar’s aides, courtiers and military officers instead fabricate an entire life for the “Lieutenant.” Besides a military career, they concoct a romance and even a marriage for him.

The fictional lieutenant rises high in the Czar’s esteem and is rewarded with promotions and riches. Finally, the Czar’s aides devise a way to “kill off” the non-existent lieutenant, and he is buried with military honors.

By 1937 Prokofiev reworked the movie score into a substantial five-movement suite, each depicting a scene from the fictional lieutenant’s life. It begins with the “Birth” of Kijé, featuring a far-off trumpet solo and martial music.

This is followed in succession by a Romance based on a love song (featuring a double bass solo); Kijé ‘s marriage, with a flourish of brass, pomp and ceremony, followed by a lively trumpet tune; the famous Troika, evoking a winter sleigh ride in the snow; and, finally, Kijé ‘s death and burial, in which brief passages from the other movements serve as reminiscences of his fictional “life.”

The suite ends as it began, with a trumpet solo in the distance.

20th Century, Suite, Works

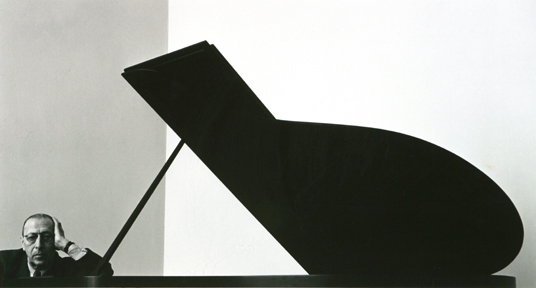

Stravinsky orchestrated this suite for small orchestra based on simple tunes he initially composed for the piano between 1914 and 1917. It is one of many “miniature” works that Stravinsky composed during his life, experimenting with various combinations of instruments, styles and textures.

This short work is in four movements — an opening calm Andante; the rollicking “Napolitana,” evoking an Italian street song and featuring woodwinds; an intense Española, with jagged rhythms, offbeats and contrasts; and the final Balalaȉka, tuneful throughout, with an abrupt ending.

20th Century, Concerto, Works

This happy, exuberant piece was composed by Shostakovich in 1957 for his son Maxim’s 19th birthday. It was premiered that year by the Moscow State Philharmonic, with Maxim as the piano soloist after his graduation from the Moscow Conservatory.

The work is in three movements. The woodwinds start the sprightly allegro, quickly joined by the piano in the opening four-note theme, with bursts of hammering percussive passages.An introspective lyrical second theme follows, with the piano accompanied by soft strings. A development section and return to the initial theme bring the movement to a close.

The middle movement is by turns wistful, poignant and lyrical, with singing piano themes that evoke late 19th-century romanticism. The piano opens the final sparkling allegro with octave-based flourishes and scales. Following that, a rollicking second theme (in 7/8 time) is heralded by the winds, in turn picked up by the piano and the strings.

On a pedagogical note, Shostakovich included many scale and arpeggio passages ‑ based on piano exercises by Louis Hanon ‑ to make sure that Maxim would learn them! Those passages are in turn echoed by the strings. A recap of the main theme, strong brass-led chords, and a timpani flourish bring this sparkling concerto to its close.

20th Century, Ballet Music, Works

In 1942, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo commissioned the choreographer Agnes de Mille to create a ballet for its 1942-43 season. De Mille came up with a concept for a ballet based on a western theme: a gathering of cowboys and ranch hands at a Saturday afternoon rodeo, together with neighbors and a lonely cowgirl.

She chose Aaron Copland, already a recognized master of the American idiom, to write the music.

The ballet was premiered at the Metropolitan Opera that same year and was an instant hit. A few years later Copland fashioned the ballet music into an orchestral suite. The suite is in four movements: Buckaroo Holiday, Corral Nocturne, Saturday Night Waltz, and Hoe-Down.

Copland used a number of American folk tunes in Rodeo. These include “If He’d be a Buckaroo” and “Sis Joe” in the opening lively Buckaroo Holiday; “Goodbye, Old Paint” in the Saturday Night Waltz; and “Bonaparte’s Retreat” and “McLeod’s Reel” in the exuberant Hoe-Down.

20th Century, Concerto, Works

My CONCERTO in the old style FOR THREE SOLO VIOLINS AND STRING ORCHESTRA was commissioned in 1994 by Marc Mostovoy for a group he founded, directed and conducted called the Concerto Soloists of Philadelphia (now called the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, resident at the Kimmel Center). I completed the work in 1994 and dedicated it to Marc Mostovoy and his Concerto Soloists, who successfully premiered the work on January 8, 1995, at the Church of the Holy Trinity in Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia. The solo violinists were Elizabeth Kaderabek, Richard Amoroso and Jennifer Haas. Tonight’s performance, with solo violinists Muneyoshi Takahashi, Kinga Augustyn, and Tzu-En Lee, will be the second performance of the work and a New York premiere.

For several years before the Philadelphia commission, I had been contemplating writing a concerto “in the old style.” Such a work by a contemporary composer is not as unusual as one might think. Many other composers have written works in the style of a previous era. This list would include such composers as Schoenberg, Prokofiev, Hindemith, Brahms, Stravinksy, Resphighi, and even Haydn. Since I had done a great deal of research into the music of the 18th and 19th centuries, I thought I would like to write a concerto grosso in the baroque style. I was delighted when the opportunity presented itself with the 1994 Mostovoy commission.

When I had completed my three-movement concerto, it turned out to be wholly original, albeit with obvious shades of Bach, Vivaldi and Townsend. The Bach and Vivaldi influences are clearly evident in the first and second movements, while Townsend predominates in the third (final) movement.

Structurally, the FIRST MOVEMENT is in a large three-part form with the first section being a statement of themes, the second section being a contrasting section (a kind of development section), and with the third section being a recapitulation of the themes of the first section.

The SECOND MOVEMENT is a Siciliana, which was a type of slow dance favored by Baroque composers for the slow movements of their concertos. This movement is in a kind of two-part form, where each part is repeated, yielding four sections (ABAB-Coda). The first section is the Siciliana theme itself, followed by a repeat of that theme by the piano. The second section is a contrasting section, played largely by the three solo violins. The third section is a repeat of the Siciliana theme in the first section. This is followed by a fourth section which is a repeat of the second section (which repeat also serves as a coda to the movement).

The THIRD MOVEMENT is in the classical rondo form, very much favored by Baroque and Classical composers. A (theme), B (contrasting section), A (theme), C (contrasting section), A (theme and coda). A large part of the C section has two of the three solo violins playing fast notes, while the first violin plays a more sustained lyrical melody. This style was favored by Bach and Vivaldi in the last movement of their concertos. Technically, in some places, the C section has the three solo violins playing in three different keys and three different rhythms all at the same time. This is strictly Townsend, and was not influenced by Bach or Vivaldi.

Notes by Douglas Townsend, NYC

20th Century, Symphony, Works

The Ninth Symphony is emblematic of the high-wire act required of a Soviet composer under Communist rule. Shostakovich’s transcendent musical gifts won him status as the Soviet Union’s leading composer, a stint as the president of the composers’ union, and international acclaim, despite two periods when he was out of favor with officialdom at home. As a young man, he ardently embraced socialist ideals, but later, after successfully responding to political criticism from the state with his Fifth Symphony, he tried to remain above the political fray. Even when he was out of favor with the Communist regime, he was never dispatched to the gulags. He remained an economically favored hero of the Republic with a country dacha and an active social life with his musical colleagues. In public, he never criticized Stalin or the Soviet government, but in private life he mocked the bureaucracy and its heavy-handed interventions in the creative process. As a result, a sarcastic tone permeates the Ninth Symphony.

Composed near the end of World War II in honor of the military victory in Europe (VE Day—May 8, 1945), Shostakovich adopted a surprisingly transparent neo-classical approach supplemented with a bombastic sneer. Reputedly, he was inspired by playing piano four-hand reductions of Haydn symphonies on a nightly basis with his friend and fellow Soviet composer Dmitri Kabalevsky. Yet Haydn never used low brass and percussion the way Shostakovich does in the Ninth. That enables the Russian to infuse his symphony with a frantic, 20th-century edge that many have interpreted as subversive. Although initially well received, the symphony was banned in his home country in 1948 and not reprieved until 1955.

The Ninth Symphony is divided into five movements. The first, an Allegro in sonata form, is crisp and bouncy, with the upper parts classical. A snare drum adds a brisk military air, and the trombones add some insistent bombast. But even the very neo-classical upper parts, chock full of short, precise notes, are skewed with a scattering of extra beats, giving the rhythm a scrambled, off-balance feel. The Moderato movement opens with a plaintive clarinet solo, later taken up by the flute. It is very Russian sounding. Tension builds as the strings take up a slightly drunken-sounding ascending scale theme. The lonely flute and clarinet return with pizzicato string accompaniment, the theme is passed to the trombone, and the strings let out a descending sigh.

The Presto reprieves the rising and falling scales but against a very different them—evoking a bouncy, balletic tip-toeing with racing clarinet and piccolo. A heroic trumpet solo blasts through. The movement is followed immediately by a Largo, introduced by a melodramatic brass chorale, giving way to a mournful bassoon solo, which some identify as a Jewish theme, perhaps in protest of Stalin’s pogroms. The movement comes to a false cadence, then transitions into the Allegretto, starting with a playful bassoon romp, then building into a triumphal, mad rush to the end.

Notes by Emily S. Plishner

20th Century, Songs, Works

Canteloube (1879-1957) was born in the Ardèche region in southern France. Early on he showed a proclivity for musical composition and eventually studied in Paris.

While he composed two operas and a number of other works, he is best known today for his settings of French folk songs, particularly those from the Auvergne region in south-central France, a rural and mountainous region. He arranged six “series” or books of these songs; the ones we’re performing today have been selected from books 1-4, composed in the 1920s. They can be sung either in the “Auvergnat” dialect (based on the medieval Occitan language — the “langue d’oc”), or in French. We’ve chosen to perform them in Auvergnat because its piquant flair fits so well with the music.

The songs themselves feature mostly country themes — a shepherd pleading with a shepherdess to come to him over the river, pledging to her his devoted love (Pastourelle); a girl’s scornful rejection of a hunchback’s offer of love (Lou Boussu); a haunting duet sung by a shepherdess and shepherd, echoing across the mountains — the shepherd finally promising to cross the river to her (Bailèro); a warning that drinking spring water is fatal — a maiden should drink wine instead, especially if she wants to get married (L’Aïo de Rotso); let’s find a meadow to graze our flocks and make love (Ound’ Onorèn Gorda?); and a hymn of praise to the beautiful girls, and to the gallant and faithful men, of the Auvergne (Obal din lou Limouzi).

20th Century, Tone Poem, Works

A gifted and eclectic composer, Griffes was born in western New York in 1884 and died prematurely in 1920 at the age of 35.

Although he studied with German pianists and composers, he was most influenced by early 20th-century French and Russian composers, and by oriental music. He developed his own unique style of American Impressionism, which clearly comes through in his Three Tone Pictures.

He originally composed these pieces for solo piano in 1915, and then orchestrated them for small ensemble. An avid devotee of poetry, he chose the titles of these atmospheric pieces from texts in three poems – William Butler Yeats’ The Lake at Innisfree (“The Lake at Evening”); Edgar Allan Poe’s The Sleeper (“The Vale of Dreams”), and Poe’s The Lake (“The Night Winds”).

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Vittorio Giannini (1903-1966) was an influential American composer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. He served on the composition faculties of the Juilliard School, Manhattan School of Music, the Curtis Institute, and the North Carolina School for the Arts; among his students were many prominent American composers, including John Corigliano, David Amram, and Nicholas Flagello.

A prolific composer in a neo-romantic style, Giannini wrote numerous symphonies, over 12 operas, works for concert band, songs, concertos and chamber works; his most enduring success was an opera buffa adaptation of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew. His compositional style grew darker and more complex towards the end of his life, and this is reflected in his Psalm 130, a work of anguish and passion – and a tour de force for the double bass.

Giannini composed the Psalm in 1963 when he was in the midst of being divorced from his young wife, and he poured his soul into this piece. The Psalm is in three sections. It opens with a declamatory statement in the high winds and strings, based on a minor seventh, which is the work’s main theme. The middle section is slower, wistful, and somber, with the soulful double bass line set off against plaintive woodwind motifs. The third section returns to and intensifies the opening theme, interspersed with double bass recitatives, before coming to an abrupt and intense end.

20th Century, Occasional Piece, Works

This work is considered by many to be among Vaughan William’s finest compositions.

Its theme is taken from a tune composed by Thomas Tallis, a 16th-century English renaissance composer. Vaughan Williams came across the tune when editing the English hymnal in 1906. When Vaughan Williams edited the hymnal, he assigned a later text to it (John Addison’s “When rising from the bed of death”), and made it the basis for the Fantasia.

The orchestration is unusual. There are two string orchestras – a first “large” orchestra, and a second small “shadow” orchestra, physically separate from each other; a string quartet; and violin and viola soloists.

The Tallis theme is initially foreshadowed by plucked lower strings, before its full exposition, first in a calm mode by middle voices, then in an impassioned mode by the first violins. An introspective viola solo leads to a rich development, in which the large orchestra’s lush sound is echoed by the “shadow” orchestra, with interplay between the string quartet and both orchestras. After a climax (based largely on the second part of the Tallis tune), the work ends with a wistful repetition of the main theme, a soaring solo violin line, one last climax, and a slow fade away.