Classical, Concerto, Works

The fifth concerto for violin, K. 219, is one of a series of great works for Mozart’s “other” instrument. We associate Mozart, and rightly so, with the keyboard. But Mozart’s skills on the violin were quite accomplished. Scholars believe Mozart performed his own violin concertos.

This concerto was written in 1775, while Mozart was in his less-than-happy tenure in his home town of Salzburg. This period of Mozart’s output saw early successes in opera and a massive output of concertos — all five recognized violin concertos were written in 1775, in addition to the first of the great piano concertos.

The concerto begins with a fast orchestral introduction. The violin solo, however, enters in a more Haydn-esque, adagio tempo. What is unusual is that not only is the tempo momentarily changed, as if the violin solo entered suspended in time, but instead of the grand, pompous slow introductions of Haydn, this is almost like inserting a slow concerto movement right into the beginning of the piece. Everything picks up again quickly, and the violin solo plays a new theme, overlaid exactly on the material of the first orchestral introduction. This ability of Mozart’s reminds the listener of Bach, where the composer can have a complete musical idea or create an entire pre-existing movement, then add still another layer of music to this music, the final product working just as well as the original. (Mozart dramatically demonstrated this concept in his own arrangement of Handel’s Messiah.)

The slow movement of this concerto contains impossibly genial, nearly polyphonic textures and harmonic treatments, all within a framework of seemingly effortless, sublime “galant” grace.

The third movement carries the idea of sections with contrasting moods and tempi further. The easy triple meter gives way to an “alla turca” section, which some believe to be actually more Hungarian-inspired than Turkish.

Classical, Concerto, Works

This is one of Haydn’s best-known concerti, and one of the most famous works for trumpet. Haydn composed it in 1796, and made full use of the solo ability of the chromatic trumpet, which had just come into its own.

The concerto is scored for large orchestra and displays the full panoply of Haydn’s mature orchestral style. An opening stately allegro gives the trumpet full reign to display melodic and technical prowess. The short slow movement features a beautiful opening melody in A-flat played by the strings and repeated by the trumpet, and displays an astonishing variety of harmonic invention.

The witty last movement, in rondo form with running passages by soloist and orchestra, closes out this work in dramatic style.

Classical, Solo with Orchestra, Works

This is one of 6 famous concertini originally attributed to the Italian composer Pergolesi. These works were first published in Holland in 1740, but without mention of a composer. Recent scholarship has discovered that all of these works, far from being the work of an Italian, were actually composed by a Dutch nobleman, Unico Wilhelem Graf Van Wassenaer. He had permitted his court violinist, Carlo Ricciotti, to publish them, but only on condition that he (Van Wassenaer) was not associated with them. (Perhaps he did not wish his noble reputation to suffer by being so closely associated with the music profession.)

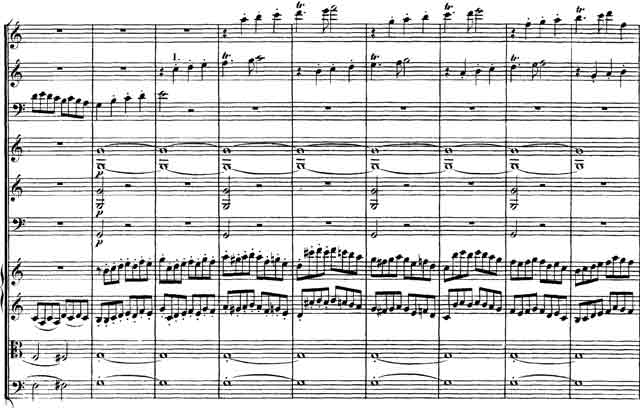

This concertino, like all of the others, is Italianate in style, with richly worked-out counterpoint and lush 7-part string writing (including 4 separate violin parts in Neapolitan style). The movements are alternately slow and fast, with a stately introduction, a fast alla breve second movement, followed by a slow third movement in “sicilienne” style.

Stravinsky adapted the last movement, in fast 6/8 time, as the basis for the “Tarantella” movement in his Pulcinella Suite.

Classical, Symphony, Works

In an astonishing burst of energy, Mozart composed his last 3 symphonies (Nos. 39, 40 and 41) in 1788 in a space of just six weeks.

The last of these three, the “Jupiter,” is grand and majestic in style. Written in C Major, it is complex in structure and form, as well as in its exploration of keys and harmonies. An imposing 5-note initial theme opens the work, setting the stage for rich musical development, alternately elegant and impassioned.

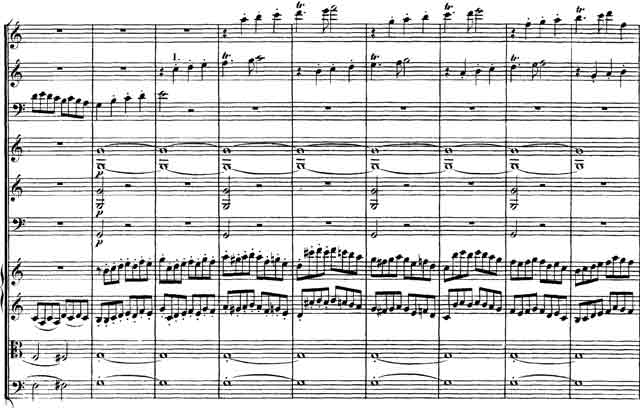

The poignant Andante cantabile opens with a lyrical rising theme by the muted violins. It is taken up in turn by the other instruments and interspersed against running scale-like passages.

After a refined Menuetto and Trio, the magnificent last movement opens with a transparent four-note theme in the violins. From this seemingly simple beginning, other themes are introduced, all of which in turn Mozart weaves into a complex tapestry of musical counterpoint. The total effect is at once grand, elegant, extraordinarily complex, and musically fulfilling.

Classical, Symphony, Works

In 1790, just two months after the death of Haydn’s employer, Prince Nikolaus Esterházy (for whom Haydn served for more than 40 years, with only brief interruptions), the violinist and impresario Johann Peter Salomon arrived in Vienna to convince Haydn to travel with him to London.

Haydn, now without permanent work and living as a freelance artist, agreed and made the first of two visits to London, composing six symphonies for this event. He paid a second visit for the 1794/1795 season, and again the principal event was a series of concerts with six new symphonies.

In contrast to his small orchestra at the Esterházy estate, the London orchestra of Salomon was a full-sized orchestra, providing Haydn with new possibilities. As a result, he composed the 12 symphonies (nos. 93-104) that count among the best he had ever written: The London Symphonies.

When Haydn finally returned to Vienna, in 1795, it was as a financially and artistically successful composer.

First performed in 1794, Symphony No. 101 is part of these famous London Symphonies, composed for his second stay in London. The second movement is responsible for the symphony’s nickname, “The Clock”: you can hear the clock-like tick-tack, introduced by the bassoons and string pizzicato, throughout the movement.

Classical, Symphony, Works

Arriaga, who lived from 1806 to 1826, showed an early talent for a musical career. Known as “the Spanish Mozart,” he was born in Bilbao in northern Spain, and composed his only opera (Los Esclavos Felices) at the age of 14.

Arriaga’s talent so impressed Bilbao’s notables that they sent him to study in Paris in 1821, where he composed three string quartets and this symphony before his untimely death from tuberculosis at age 19.

Arriaga wrote his Symphony in D Major in 1824-5. It is a work with decided influences reminiscent of Schubert and Mozart, especially in its use of keys and harmonies. The opening adagio intersperses solo wind passages with brooding string motifs; this segues into an impassioned allegro, dramatically in the minor key. The andante is conventionally classical in form, but shows an inventive use of woodwinds and unusual string passagework. A minuetto and trio follows, the latter with solo flute and guitar-like string pizzicato effects.

The last movement opens again in the minor key, with an Italianate violin theme. A delightful second theme follows (again in the violins). A return to the major key heralds the triumphant finale.