“New World” Symphony

Czech composer Antonin Dvořák was born in a village near Prague. Despite his father’s wishes for him to continue in the family business and become a butcher, Dvořák pursued his career in music and by the age of 18 was working as a fulltime musician. During his childhood he developed a deep passion for his heritage and fell in love with the native folk tunes and bohemian melodies associated with his village. It was these early influences that shaped Dvořák’s style. Much of his repertoire is based on Bohemian folk songs and melodies.

Dvořák moved to New York in 1892, after he was named the Director of the National Conservatory of Music. He lived not far from there, at 327 E. 17th Street, just down the street from where the Conservatory used to be (there is a high school there now). It was there that the “New World” Symphony and the Cello Concerto in B Minor were written. The “New World” was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and premiered in December of 1893 at Carnegie Hall. Because of his love for folk music, Dvořák was very interested in Native American and spiritual melodies and themes, and said upon his arrival here, “I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America and your composers must turn to them.”

Dvořák said of the “New World” the day before its premiere, “I have not actually used any of the [Native American] melodies. I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of the Indian music and, using these themes as subjects, have developed them with all the resources of modern rhythms, counterpoint, and orchestral color.”

Throughout this piece, the listener can pick out the influence of these themes on the symphony. The main theme in the second movement is perhaps the most famous melody that Dvořák wrote and has been used widely in TV and Film scores. It was played during the coverage of the landing on the moon and subsequent celebrations of that event.

“Tragic” Overture

Johannes Brahms composed The Tragic Overture, Op 81 in the fall of 1880 as a companion to the Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 written a few months earlier. In a letter to Karl Reinecke, Brahms wrote: “one [overture] weeps while the other laughs”.

According to the writer and music critic Max Kalbeck, the Tragic Overture was inspired by Goethe’s Faust for which Brahms is said to have intended to write incidental music (a claim denied by the composer). The dramatic and contrasting character of the two main themes of the overture is more than evident and the themes’ very individual and character-like qualities support Kalbeck’s claim.

The formal organization of the overture also seems to support Kalbeck’s theory. The two main themes are both “square” with their 8-measure structure and both have their preliminary development in the exposition. The development section is designed as a separate section with its own austere (Molto Piu Moderato) character. It borrows material from the first theme of the exposition, but is reshaped in a completely different manner. Another interesting moment in the overture is the beginning of the recapitulation where the first theme is omitted in favor of a differently orchestrated second theme.

The overture ends in a manner similar to the ending of Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony – a deceptive retreat, followed by sudden intensity.

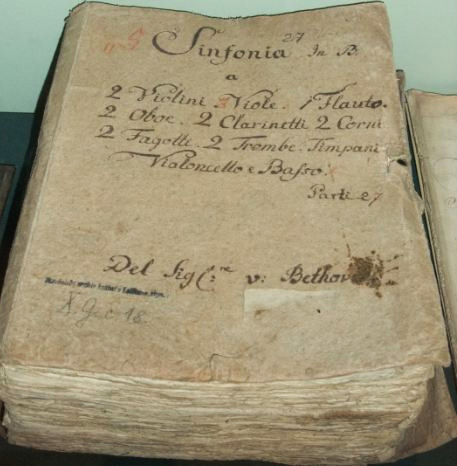

Symphony No. 4 in Bb Major

Beethoven composed his Symphony No. 4 in B-flat Major, Op. 60 in the summer and the fall of 1806. 1806 was one of the most productive years of Beethoven’s entire life. During this year, he completed his Piano Concerto No. 4, the Violin Concerto, Leonore Overture No. 3, Coriolan Overture, the Three Rasumovsky String Quartets, the Piano Sonata No. 23 “Apassionata” and the 32 Variations on a Original Theme in C minor.

Beethoven conducted the first private performance of the symphony at the home of Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz in Vienna in 1807, and the first public performance in April 1808, in Vienna’s Burgtheater.

Although not as popular and not as frequently performed as the Third and the Fifth, the Fourth Symphony has a unique place in Beethoven’s catalogue. Today’s audiences, perhaps swept away by the works’ tragic and heroic power, tend to prefer the odd-numbered symphonies. However, Beethoven’s even-numbered symphonies show equally profound and beautiful aspects of his genius. In a critical study of Beethoven’s symphonies, Berlioz said of the Fourth Symphony: “The general character of this score is either lively, alert and gay or of a celestial sweetness.” Robert Schumann compared the work to “a slender Grecian maiden between two Nordic giants,” having in mind the sequence of the Third, Fourth and the Fifth symphonies.

The first movement of the Fourth Symphony opens with a slow introduction (Adagio) in which we have the feeling that the time is standing still. The cold and motionless music from the introduction is “detonated” by the flamboyant chords of the sonata allegro (Allegro vivace) giving energy to a joyous and Haydnesque movement almost entirely based on the opening staccato notes of the first theme.

The second movement (Adagio) brought Berlioz to exaltation — “Its form is so pure and the expression of its melody so angelic and of such irresistible tenderness that the prodigious art by which this perfection is attained disappears completely.”

The third movement (another Allegro vivace) is based on the constant juxtaposition between duple and triple pulse. The entire movement is repeated twice, thus becoming a model for Beethoven’s Fifth and Seventh symphonies.

The fourth movement (Allegro ma non troppo) returns to the sparkling and playful mood of the first movement. Here sudden dynamic contrasts and furious passages in sixteenths become the moving forces. At the end of the movement, Beethoven again pays homage to his teacher Haydn by lulling the listener to repose before the final outburst.

Pelleas et Melisande

Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande tells the story of Golaud who encounters the mysterious Mélisande in the forest, and marries her. But very soon, Mélisande finds her true love in the person of Pelléas, Golaud’s half-brother. Golaud becomes suspicious of the lovers, killing Pelléas and wounding Mélisande. Mélisande dies in childbirth, and Golaud continues his descent into madness.

In the twelve years following the play’s 1893 premiere in Paris, four great composers wrote music inspired by Maeterlinck’s masterpiece – Claude Debussy (opera), Gabriel Faure (incidental music), Arnold Schoenberg (symphonic poem) and Jean Sibelius (incidental music).

After Debussy completed an early version of his opera in 1895, British actress Mrs. Patrick Campbell (soon to play the role of Mélisande in London), requested Debussy to excerpt a symphonic suite from the opera to accompany the play’s London production. Debussy refused. Mrs. Campbell then asked Faure to write incidental music to Maeterlinck’s play. Faure agreed. After a one-month collaboration with orchestrator Charles Koechlin, the score of the Incidental Music to Pelléas et Mélisande, Op. 80 was ready. Maeterlinck, present at the 1898 London premiere of the translated play — accompanied by Faure’s incidental music — wrote to Mrs. Campbell, “In a few words, you filled me with an emotion of beauty the most complete, the most harmonious, the sweetest that I have ever felt to this day.”

The orchestral suite consists of four numbers — Prelude (the prelude to Act I in Faure’s complete orchestral score), La Fileuse (Mélisande at the spinning wheel), Sicilienne (the actual prelude to Act II with one of the most famous flute solos in the symphonic repertoire) and La Mort de Mélisande (the Prelude to Act III).

Haydn Variations

The third of the “Three B’s” (along with Bach and Beethoven), Brahms adhered to the use of classical forms in his works but dramatically altered the musical landscape in terms of harmony and expressiveness. Included among Brahms’s masterpieces are four symphonies, two orchestral serenades and two overtures, much great chamber music and many pieces for piano, assorted concertos, the Hungarian Dances, the German Requiem and other choral works.

Given the preeminence that Brahms holds today as an orchestral composer, it is somewhat surprising to find that he did not have a single work in the orchestral repertory until he was nearly 40, and it was the brilliantly crafted “Haydn Variations” that helped secure his reputation as a symphonist. Brahms produced two separate versions of the work: the present one for orchestra and a second one for two pianos. Although the pieces are effectively identical, Brahms considered them two independent works rather than viewing one or the other as a transcription. Brahms himself premiered the piano composition in August 1873 with Clara Schumann. The orchestral composition had its premiere in November of the same year.

Notes by GHR

Variations on a Rococo Theme

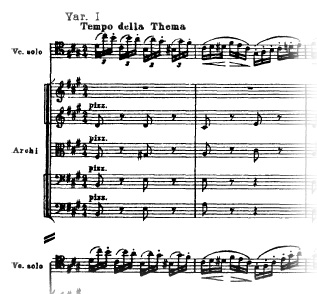

Tchaikovsky composed the Variations on a Rococo Theme in December of 1876, amidst the turmoil of a failed opera production in St. Petersburg and a particularly nasty review in Vienna from the feared critic Eduard Hanslick. Prone to insecurity even at the best of times, Tchaikovsky asked for advice from the new work’s intended cello soloist, Wilhelm Fitzenhagen. Just 28, Fitzenhagen was a professor at the Moscow Conservatory and principal cellist for the Imperial Russian Music Society. He also fancied himself a composer, and his “corrections” to the work of his well-established colleague show surprising aplomb. Fitzenhagen rearranged the order of the variations,

removing one entirely, and rewrote most of the solo part. Tchaikovsky accepted the changes, and the hybridized version entered the popular canon, thanks to Fitzenhagen’s numerous concert appearances and an 1889 publication. 20th-century scholarship (aided by X-rays) revealed Tchaikovsky’s original music under Fitzenhagen’s emendations, and a reconstructed version debuted in Moscow in 1941. By then, Fitzenhagen’s edition had cemented its reputation among cellists and audiences, and it continues to be the customary choice for performances.

The Variations on a Rococo Theme reference the 18th Century — especially Mozart, whom Tchaikovsky adored. The theme is Tchaikovsky’s own invention, and it has little relation to the ornate Rococo style that emerged in France under Louis XIV, a movement that produced gilded palaces and the trill-happy music of Couperin. Following a stately orchestral introduction, the cello introduces the light-stepping “rococo” theme, balanced into two repeated sections. The theme ends with a harmonically adventurous codetta, first in the winds alone and then shifting to the strings. That material returns various times to link the connected variations, and it brings Tchaikovsky’s rich Romantic voice into dialogue with the lean Classical ideals explored elsewhere in the work.

The first two variations maintain the theme’s flavor and pulse, adding increasing decoration and commentary. The third variation breaks away to a singing melody, one of those heartbreaking tunes that Tchaikovsky unfurled with such ease. The fourth and fifth variations return to an outgoing, virtuosic character, culminating in an extended cadenza. The sixth variation, a minor-key andante, bookends the earlier slow section, and trails off in an ascent of ethereal harmonics. The final variation follows the work’s only pause, and enters with a rustic, throbbing intensity. It intensifies through quick call-and-response phrases and breathless figurations, linking directly to the energetic coda and a rousing conclusion.

Copyright © Aaron Grad 2011

Symphony No. 9 in Eb Major

The Ninth Symphony is emblematic of the high-wire act required of a Soviet composer under Communist rule. Shostakovich’s transcendent musical gifts won him status as the Soviet Union’s leading composer, a stint as the president of the composers’ union, and international acclaim, despite two periods when he was out of favor with officialdom at home. As a young man, he ardently embraced socialist ideals, but later, after successfully responding to political criticism from the state with his Fifth Symphony, he tried to remain above the political fray. Even when he was out of favor with the Communist regime, he was never dispatched to the gulags. He remained an economically favored hero of the Republic with a country dacha and an active social life with his musical colleagues. In public, he never criticized Stalin or the Soviet government, but in private life he mocked the bureaucracy and its heavy-handed interventions in the creative process. As a result, a sarcastic tone permeates the Ninth Symphony.

Composed near the end of World War II in honor of the military victory in Europe (VE Day—May 8, 1945), Shostakovich adopted a surprisingly transparent neo-classical approach supplemented with a bombastic sneer. Reputedly, he was inspired by playing piano four-hand reductions of Haydn symphonies on a nightly basis with his friend and fellow Soviet composer Dmitri Kabalevsky. Yet Haydn never used low brass and percussion the way Shostakovich does in the Ninth. That enables the Russian to infuse his symphony with a frantic, 20th-century edge that many have interpreted as subversive. Although initially well received, the symphony was banned in his home country in 1948 and not reprieved until 1955.

The Ninth Symphony is divided into five movements. The first, an Allegro in sonata form, is crisp and bouncy, with the upper parts classical. A snare drum adds a brisk military air, and the trombones add some insistent bombast. But even the very neo-classical upper parts, chock full of short, precise notes, are skewed with a scattering of extra beats, giving the rhythm a scrambled, off-balance feel. The Moderato movement opens with a plaintive clarinet solo, later taken up by the flute. It is very Russian sounding. Tension builds as the strings take up a slightly drunken-sounding ascending scale theme. The lonely flute and clarinet return with pizzicato string accompaniment, the theme is passed to the trombone, and the strings let out a descending sigh.

The Presto reprieves the rising and falling scales but against a very different them—evoking a bouncy, balletic tip-toeing with racing clarinet and piccolo. A heroic trumpet solo blasts through. The movement is followed immediately by a Largo, introduced by a melodramatic brass chorale, giving way to a mournful bassoon solo, which some identify as a Jewish theme, perhaps in protest of Stalin’s pogroms. The movement comes to a false cadence, then transitions into the Allegretto, starting with a playful bassoon romp, then building into a triumphal, mad rush to the end.

Notes by Emily S. Plishner

Songs My Mother Taught Me

Dvořák composed this work as part of his cycle of “Gypsy Songs” for voice and piano. This song, with its wistful and longing melody, has become famous in its own right. It has been performed in many arrangements, both by singers and instrumentalists. The words were originally set in Czech (sung in our performance today) and German. Here is the English translation (by Natalia Macfarren):

Songs my mother taught me, in the days long vanished;

Seldom from her eyelids were the teardrops banished.

Now I teach my children each melodious measure;

Oft the tears are flowing, oft they flow from my memory’s treasure.

Czech Suite

The Czech Suite was one of several works Dvořák composed for small orchestra between 1875 and 1879 (the others being his masterful string and wind serenades). While scored for a Mozart-sized orchestra (much smaller than his symphonies), it has the beauty, sweep and grandeur of Dvořák’s larger works.

The Suite is in five movements, several of which are based on Czech dance forms. A tranquil Pastorale opens this work, essentially a prelude based on a simple descending theme passed around various string and wind sections. Next come two specifically Czech dance movements — a Polka, featuring a rising graceful theme in the violins, with a lively trio; and then a country minuet (“Sousedská”), opening with a decisive statement from clarinets and bassoons.

A short lyrical romance follows, featuring upper winds (flutes, oboes, English horn) and charming wind and string dialogues.

The finale is based on a boisterous Czech dance form, the “Furiant” (also used by Dvořák in other instrumental works), full of drive, syncopation and rhythmic flourishes, and ending in a fiery dash.