20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

“Tubby,” with music by George Kleinsinger and story by Paul Tripp, was composed in 1946. It serves as a wonderful introduction to the orchestra, and has become a well-loved children’s classic.

It tells the story of Tubby, a fat little tuba who just wants to be treated like all of the other instruments of the orchestra. As the lowest-sounding instrument, Tubby usually just gets to play “oompah-oompah.” What he really wants is to play pretty melodies just like all of the other instruments in the orchestra!

When Tubby first tries to do that, the other instruments make fun of him. After rehearsal, Tubby goes home and sits sadly by a riverbank; but there, he meets a big bullfrog, who teaches him a wonderful new melody. At the next rehearsal, the conductor gives Tubby the chance to play his new melody. Tubby plays it so beautifully that all the other instruments love it and want to play it too!

Everyone joins together in the rousing finale, making Tubby a very happy tuba indeed.

Classical, Symphony, Works

In the 1780’s, Mozart’s fame was, amazingly, already fading in Vienna; but in Prague, then capital of Bohemia, Mozart was celebrated as a rock star would be today. He made a triumphant four-week trip in January of 1787, to be present at, and later conduct, performances of The Marriage of Figaro and also to perform on keyboard and conduct a symphonic concert, as well as generally just to be the toast of Prague.

So popular was Figaro that Mozart remarked in a letter that its melodies were all one heard played, even by the street musicians around Prague. Later that year, Mozart would undertake to write the opera Don Giovanni for production in the city, and his last opera, La Clemenza di Tito, would also be written for Prague.

The Symphony No. 38 has magic in every measure. His ability to retain both an overwhelming expression of his personality, plus classical stylistic grace, within a technique which allowed him to survey and synthesize influences even from different style periods, is nearly incomprehensible. In the Prague symphony, one can hear so many facets of Mozart’s musical expression and genius: total command of the symphonic style, elements of lyric and comic opera and vocally-influenced writing, a complete mastery of counterpoint, and on and on even a foreshadowing of the chromatic evolution of harmony.

The slow introduction of the first movement recalls Haydn-esque majestic treatment, but has also a developmental quality reminiscent of Mozart’s keyboard fantasias. The string color of the allegro reminds one of the opening of the beautiful symphony no. 29, but is suddenly interrupted by a spirited outdoor wind band playing a little fanfare reminiscent of “non piu andrai” from Figaro. The beautiful second movement has been said by one writer to have inspired the slow movement of Schubert’s first symphony, performed by the Broadway Bach Ensemble last year.

Unlike the late Haydn symphonies, Mozart’s Symphony No. 38 is only in three movements, as was early practice for Mozart and apparently still fashionable in Prague. Mozart’s last five symphonies are often grouped together and lauded as achieving new depth and accomplishment in the symphonic form. The wind instrument playing in Vienna at the time was said to be particularly advanced, and one can hear this in demanding passages and in the complex scoring of the symphony.

Zaslaw claims that symphonies had taken on a more serious role, that they were “expected to exhibit artistic depth rather than serving merely as elaborate fanfares to open and close concerts.” What reaches us so powerfully in the music of Mozart is perhaps his direct and disarming humanity: like many of the great ones, he had to deal with making money and relatives and on and on.

Nonetheless, his great accomplishments and proclivities in symphonic writing didn’t save him from some blunt fatherly advice. Leopold warned Wolfgang about writing at too difficult a level for orchestras. The “Father Knows Best” of his time told the composer that bad performances might result. “…for I know your style of composition — it requires unusually close attention from the players of every type of instrument; and to keep the whole orchestra at such a pitch of industry and alertness for three hours is no joke.” Well, dads will be dads, and what concerned Leopold just happens to be our delight.

20th Century, Occasional Piece, Works

Voyage is a string-orchestral version of the choral setting of Richard Wilbur’s translation of Baudelaire’s “L’Invitation au Voyage.” The lyrical, seamless vocal lines translated themselves naturally to strings, and the burnished imagery of the poetry finds a happy companion in the richness of the instrumental choir.

Romantic, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Carl Maria von Weber was one of the pioneers, if not the preeminent pioneer, of German Romanticism in music.

The Andante and Rondo Ungarese (Hungarian Rondo) was originally written, in 1809, for viola solo and orchestra. Von Weber later re-worked the piece for bassoon solo (1813), upon request of Georg Friedrich Brandt, bassoonist of the Munich Orchestra. The Andante is a set of short variations. The rondo marks one of the early points of Germanic fascination with things Hungarian in its rollicking melody and dance-like character. Later well-known examples of this fashion are Brahms’ Hungarian Dances and the finale of his violin concerto.

Concerto, Romantic, Works

Vivaldi, himself a violinist, wrote over 500 concertos, and interestingly enough, besides the 230 for violin, wrote more concertos for the bassoon than for any other instrument. Even though, like Bach, Vivaldi was forgotten for decades, the resurgence in scholarship of baroque music in the late 19th century brought him back into recognition.

In his own time, Vivaldi was actually quite influential, having established some standard-practice techniques of baroque composition and serving as a model for the young Bach. Even though he borrowed his own material liberally, as was the practice at the time, he was nonetheless very inventive, especially in string writing. He devised different expressive techniques in string articulation and bowing.

One can hear this transparently in the bassoon concerto we are performing, a graceful string texture backing up the remarkable solo bassoon fireworks and melodic display.

Overture, Romantic, Works

Schubert wrote the Overture in B flat in 1816. By this time, he had already written four symphonies and several other overtures.

Schubert was a good violinist as well as pianist and held a principal position in his school orchestra in Vienna. Legend has it that the orchestra would rehearse every night with the windows of their rehearsal room open, stopping traffic as the Viennese would pause to listen.

That Schubert was steeped in the symphonies of Haydn and Mozart, one of which the school orchestra would play every night, is apparent in both the style of Schubert’s writing, as well as his deep knowledge of the capabilities of the orchestra. Even though this lineage is readily apparent, one can also already detect Schubert’s individuality, in his ever warm mood, and particularly in his presentation of themes in even more remote keys than was usually practiced before.

20th Century, Works

Perhaps the most famous children’s work ever written, Peter and The Wolf was composed by Sergei Prokofiev in 1936 as a way of introducing children to the instruments of the orchestra.

It opens with Peter, a brave little boy (played by the strings), going out into the meadow and observing a bird (the flute) and a duck (the oboe). The bird and the duck begin talking and then quarreling. A cat (the clarinet) comes along and tries to catch the bird, which flies away. Grandfather (the bassoon) appears and is angry that Peter is in the meadow. It’s dangerous out there; if a wolf should come along, what would Peter do then? Although Peter says he is not afraid, Grandfather takes Peter back home and locks the gate. Sure enough, an enormous wolf (three French horns) suddenly appears; the wolf then chases, catches and swallows the duck.

But Peter, with the help of the bird, manages to trap the wolf with a lasso. The hunters, who had been tracking the wolf, appear and help Peter take the trapped wolf to the zoo. Peter, the hunters, the wolf, grandfather, the cat and the bird then join in the triumphal procession. Even the duck’s quacking is heard, because the wolf had been in such a hurry that he had swallowed the duck alive!

20th Century, Concerto, Works

Written in 1954, this short 3-movement work was Vaughan Williams’ last concerto.

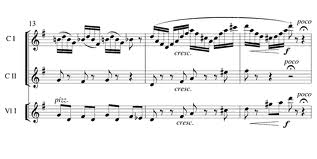

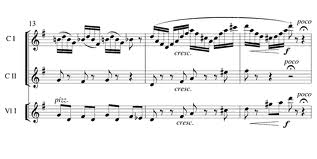

It is a compact work, with 2 modernistic outside movements surrounding a slow movement. It begins with a vigorous opening built around rising and falling scale-like passages. This is followed by a second theme (a little reminiscent of Hindemith in style), and a third, folk song-like theme.

The second movement harks back to Vaughan Williams’ earlier melodious and dreamy style. Orchestra and soloist both take part, weaving in and out of the musical fabric; the tuba’s sonorous capabilities are on full display in the scale-based theme followed by baroque-like ornamentation.

The concluding Finale is a rollicking “German rondo” (“Rondo alla Tedesca”), with a robust main theme first played by the tuba and echoed by the orchestra; the second theme is harmonically more adventurous, with a plaintive, almost urgent feel to it. After successive, ever more frenetic renditions of the 2 themes, the concerto ends in a furious dash.

The first and third movements both contain substantial solo cadenzas displaying the tuba’s range and versatility.

Classical, Symphony, Works

Leopold Mozart, the father of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was a well-known teacher and composer in his own right in mid-18th century Germany. Although he composed conventional orchestral and choral works, he also composed a number of programmatic pieces with peasant or rustic themes.

Of these, the best-known is the “Toy Symphony,” also known as the Kindersinfonie (Childrens’ Symphony) or “Sinfonia Berchtolsgadensis,” named after a village in the Bavarian Alps which was an important center for making cuckoo clocks and toy musical instruments in the 18th century.

This lighthearted 3-movement work features a small orchestra of strings, consisting of violins, ‘cellos and basses (but no violas). It also includes an assortment of “toy” wind and percussion instruments (the cuckoo, quail, nightingale, rattle, drum, trumpet and triangle), which are used with a good deal of melody, harmony and humor.

Occasional Piece, Romantic, Works

Kodály, together with Bartok, was a major figure in the collection and analysis of Hungarian folk music.

Many of Kodály’s compositions are based on Hungarian folk tunes of various types. This is evident in the “Hungarian Rondo,” which Kodály wrote in 1917 and premiered in Vienna in early 1918. Originally titled “Old Hungarian Soldiers’ Songs,” its themes are based on the verbunkós, a type of army recruiting dance which utilized gypsy bands (symbolized here by strings, supplemented with raucous clarinets and bassoons).

The verbunkós typically had alternating slow-fast sections, with punctuating codas. In the Hungarian Rondo, Kodály follows through on this tradition by interspersing the opening slow string theme, in different instrumentations (solo violin, clarinet, mixed ensembles), with increasingly frenetic gypsy melodies.