Concerto, Romantic, Works

This concerto is truly a work of superlatives.

It was the last concerto Beethoven composed, and is seen by some as the end of his “heroic” period. The title “Emperor,” although in common use now, is not Beethoven’s; it became attached to the concerto after Beethoven’s death, in 1827, probably due to the nobility and expansiveness of its themes.

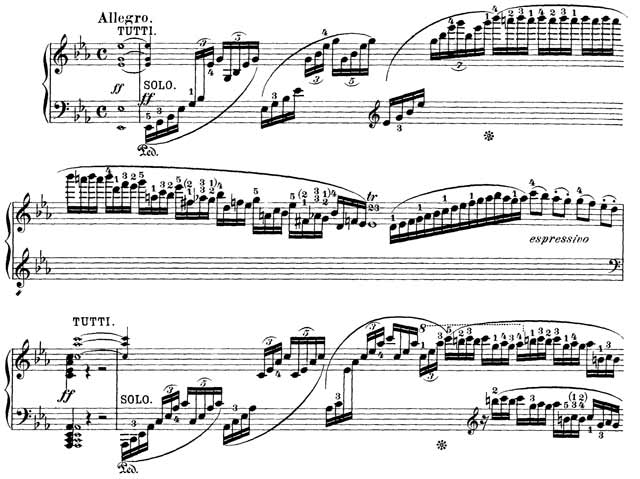

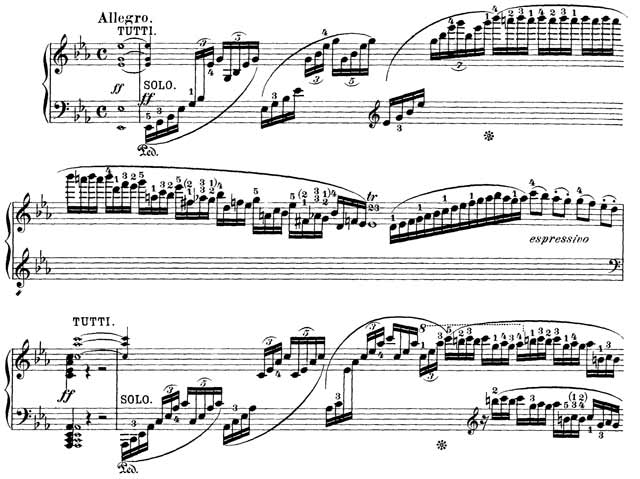

Beethoven composed this work in 1809 during the siege and bombardment of Vienna by the French under Napoleon. Due to his growing deafness, it was the first of his piano concertos where the premiere was played by a pianist other than Beethoven himself (by Friedrich Schneider in Leipzig in 1811, and by his pupil Carl Czerny at the Vienna premiere in 1812). It was also the first concerto in which a composer integrated his cadenzas into the score itself; indeed, it is notable that the piece actually starts with a piano cadenza!

After the opening cadenza, the orchestra states the familiar first martial theme, which includes a turn, descending arpeggio quarter notes, and a dotted eighth-sixteenth-half note motif, all of which make their appearance as subthemes later in the first movement. The second theme also makes its appearance in the opening orchestral tutti, in E-flat minor – a soft step-wise slow “march” immediately reprised in E-flat major as a beautiful melody played by two horns. This basic thematic material is used by Beethoven throughout the first movement, interspersed by richly ornamented piano passages and cadenzas. The key relationships are also notable. Besides the usual familiar keys (E-flat, B-flat, A-flat), Beethoven repeatedly moves into more distant keys, particularly C-flat major/B minor (with a “third” relationship to the concerto’s overall key of E-flat). Also notable are a tendency for themes to move step-wise by a half-tone into different keys.

The following adagio is in B Major (again that “third” relationship). Its opening theme is actually based upon a tune which Beethoven originally intended for a military band (!) and then magically transposed into an ethereal “pilgrim’s song.” After the opening, the theme is repeated twice, once by the piano alone, then by a flute-clarinet-bassoon choir against the piano’s accompaniment.

At the end of the adagio, a step-wise downward movement from the bassoons to the horns brings the tonality back from B major to B-flat (the fifth of E-flat). After a tentative prelude, the pianist launches full throttle into the robust last movement, a classic joyous rondo with hunting theme overtones. The rondo theme is repeated four times, and interspersed with variations by soloist and orchestra. In the coda the piano plays part of the rondo theme accompanied by the timpani. A last dash by the piano and orchestra leads to the concerto’s grand conclusion.

20th Century, Suite, Works

Falla was a quintessentially Spanish composer who partially developed his style while living in Paris, between 1907 and 1914. There he became well-acquainted with Ravel, Debussy and Dukas.

He originally composed the music for The Three-Cornered Hat in 1917 to accompany a pantomime based on a story by the late 19th-century Spanish writer Pedro Alarcón. The famous impresario Diaghilev persuaded Falla to turn the music into a full ballet, which was premiered in London in 1919, with sets by Picasso and choreography by Massine. Falla later arranged the music into two separate orchestral suites, the first of which we are performing today.

The story focuses on an ugly and misshapen miller and his beautiful wife, who is very much in love with him; the Corregidor, a local magistrate who wears a large three-cornered hat as a sign of his office; and a series of amorous pursuits and mistaken identities (with a happy ending).

After a short introductory fanfare, the piece opens to an afternoon scene in a small Andalusian village. The miller and his wife, amid their daily tasks, are trying to teach a bird to tell the time; they kiss, then dance.

Announced by the bassoon, the Corregidor appears; he is captivated by the pretty miller’s wife, but leaves the scene after a disapproving glance from his own wife. The miller’s wife dances a rousing Fandango, featuring a typically Spanish meter alternating between 3 and 2.

The Corregidor appears again; the miller’s wife politely curtsies, and then begins a flirtatious dance, teasing the Corregidor with a bunch of grapes which she keeps just out of his reach. The Corregidor stumbles and falls, and storms off. The miller and his wife dance again, reprising the Fandango theme, to end the Suite.

Baroque, Suite, Works

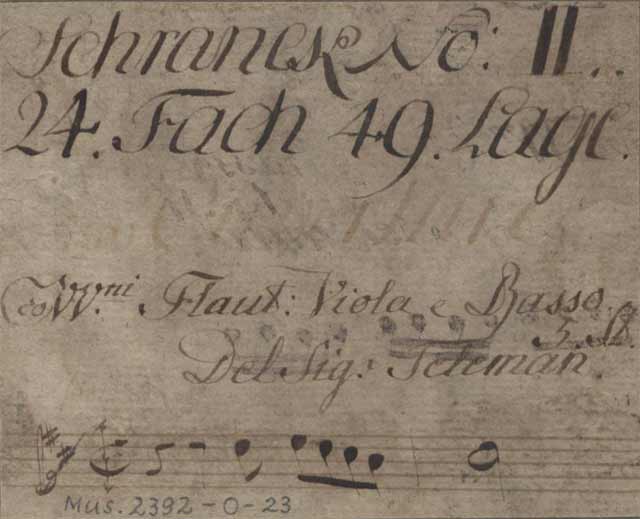

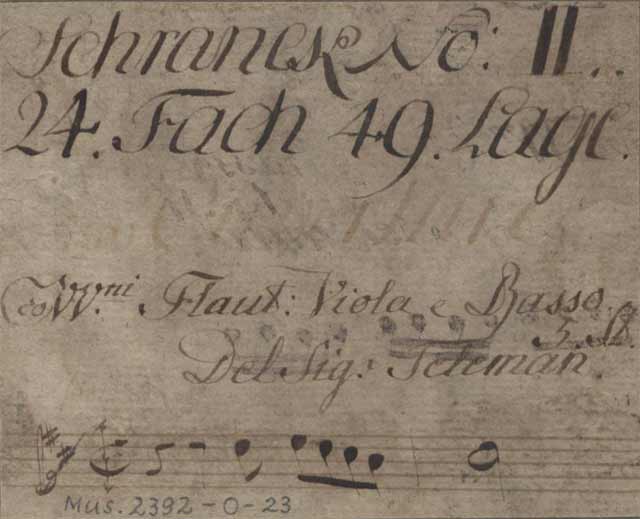

During his long and productive life (1681-1767), Telemann became one of the most celebrated of baroque composers. His output was vast, ranging from operas and cantatas to concertos and intimate chamber works.

One of his most charming pieces is the programmatic Don Quixote suite for strings and continuo. The suite opens conventionally enough, with a formal French-style baroque overture. The movements which follow, however, depict different scenes from the adventures of Don Quixote, Cervantes’ famous knight, and his squire, Sancho Panza.

It begins with the “Awakening of Don Quixote,” with string drones evoking sleep, followed immediately by the “attack on the Windmills,” with furiously rushing string passages. “Sighs for Princess Aline” features accented descending eighth notes characteristic of 18th-century passages evoking “tender” emotions. “Sancho Panza Swindled” has a rough peasant atmosphere, depicting the squire being tossed in a blanket. “Rosinante Galloping” evokes the smooth stride of Don Quixote’s horse, while “The Gallop of Sancho Panza’s Mule” shows the ungainly “start-stop” step of the squire’s transport. The Suite closes with “Don Quixote at Rest,” also featuring string drones.

Classical, Concerto, Works

This is one of Haydn’s best-known concerti, and one of the most famous works for trumpet. Haydn composed it in 1796, and made full use of the solo ability of the chromatic trumpet, which had just come into its own.

The concerto is scored for large orchestra and displays the full panoply of Haydn’s mature orchestral style. An opening stately allegro gives the trumpet full reign to display melodic and technical prowess. The short slow movement features a beautiful opening melody in A-flat played by the strings and repeated by the trumpet, and displays an astonishing variety of harmonic invention.

The witty last movement, in rondo form with running passages by soloist and orchestra, closes out this work in dramatic style.

20th Century, Occasional Piece, Works

Ives is one of America’s most intriguing composers. He began his musical studies under his father (a bandmaster), became an organist for a Connecticut church, and began composing around the turn of the 20th century. After graduating in 1908 from Yale University, Ives went into a successful career in the insurance business, but continued his composing activities.

Widely ignored until the end of his life, Ives is now an established American composer. His style is pioneering and eclectic, and runs the gamut from beautiful melody to wild dissonances and polyrhythms.

He wrote his original version of The Unanswered Question around 1906, and revised it between 1930 and 1935. The work is scored for strings, solo trumpet and wind choir (2 flutes, oboe, and clarinet).

While the strings play a slow soft chorale, the solo trumpet asks a series of “questions.” Each time, the wind quartet answers the trumpet. While the first “answers” are slow, they rapidly increase in intensity, tempo and urgency. After a final shrill burst from the winds, the trumpet repeats the question, letting it hang in the air until the end of the piece.

20th Century, Suite, Works

Ravel first composed Tombeau as a suite for piano in six movements, and then arranged it as a 4-movement suite for orchestra in 1919.

A “tombeau” was, in the French baroque tradition, a composition meant as a memorial, and each movement of Ravel’s Tombeau is dedicated to a friend who perished in World War I.

The reference to “Couperin” evokes one of France’s great baroque composers, and indeed the four movements of this work are based largely on baroque French dance forms. Ravel’s genius is to fuse these baroque frameworks with modern harmonies and instrumentation to create works of atmosphere, charm and grace.

The opening Prélude is a cascade of motifs led by the oboe (which has a virtuosic part in this entire work). The dance movements all have main sections with contrasting interludes. The Forlane is a wistful modern rendering of a stately dance, evolving into ever more unearthly harmonies until its resolution; the Menuet is a charming updating of an old classic; and the Rigaudon, with woodwind and brass highlights, provides a rousing finale.

Romantic, Symphony, Works

Ludwig van Beethoven was aware that he was following in the footsteps of giants as he began composing his first symphony. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, already dead eight years in 1799, had blazed across the musical firmament like a meteor, leaving lesser composers despondent and scrambling to incorporate his stylistic innovations. Franz Josef Haydn, still active in Vienna, was famous as the “Father of the String Quartet” and brought the symphony to a perfection recognized in all the capitals of Europe.

Beethoven’s first effort at symphonic writing built squarely upon the work of these two models: four movements in the order Fast-Slow-Minuet-Fast; a texture in which the melody dominates, but with digressions into the older, contrapuntal style; harmonies which were clearly delineated, changed slowly, but served always to propel the music forward; above all, a sense of balance and proportion in all the aspects of composition. What Beethoven could only have suspected, but that we now know, is the craft, inspiration, power, and vigor that he poured into the form handed down to him.

The work we hear today is in no sense a youthful experiment, but it is instead a fully-developed masterwork by a young genius, and has earned a place among the great monuments of musical art.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Both Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Ralph Vaughan-Williams were intensely interested in the folk music of their native soil. Each composer attempted to create a distinctive national style by incorporating local folk tunes, rhythms, and harmonies into their art.

The two works that we are to hear today are excellent examples of this process. “The Lark Ascending” draws its inspiration from the mysticism of the English countryside, setting several folk tunes in a quiet manner, conveying a calm, peaceful and transcendent mood to the listener, with the solo violin observing and commenting on the scene from afar. The work begins and ends with meditative reveries from the solo violin.

The “Fantasy on Russian Themes” sets the solo violin in an active mode, with the brilliance and power to compete directly with an exuberant orchestra. Here, too, the violin is given solo moments of an improvisational nature, but rather than the inward-looking ruminations of the “Lark,” we are presented with what are merely lyric interruptions in an otherwise boisterous, robust scene of a country gathering. Here joyous peasants participate in the highly social activities of dancing, singing and drinking among family and friends.

The two works together are an interesting study in contrast, and provide an enchanting view into two artistic minds as they envision a showcase for the solo violin.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Both Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Ralph Vaughan-Williams were intensely interested in the folk music of their native soil. Each composer attempted to create a distinctive national style by incorporating local folk tunes, rhythms, and harmonies into their art.

The two works that we are to hear today are excellent examples of this process. “The Lark Ascending” draws its inspiration from the mysticism of the English countryside, setting several folk tunes in a quiet manner, conveying a calm, peaceful and transcendent mood to the listener, with the solo violin observing and commenting on the scene from afar. The work begins and ends with meditative reveries from the solo violin.

The “Fantasy on Russian Themes” sets the solo violin in an active mode, with the brilliance and power to compete directly with an exuberant orchestra. Here, too, the violin is given solo moments of an improvisational nature, but rather than the inward-looking ruminations of the “Lark,” we are presented with what are merely lyric interruptions in an otherwise boisterous, robust scene of a country gathering. Here joyous peasants participate in the highly social activities of dancing, singing and drinking among family and friends.

The two works together are an interesting study in contrast, and provide an enchanting view into two artistic minds as they envision a showcase for the solo violin.

Concerto, Romantic, Works

The years from 1720 to 1750 were, from the perspective of the present, dominated by Johann Sebastian Bach; but for a musically aware person of the period Georg Philipp Telemann was the foremost musician of his day. His music, while firmly rooted in the contrapuntal intricacies of the Baroque style, served as a bridge between the old methods and the emerging Classical style of simple textures, clear harmonies, and elegant melodies.

Telemann founded the first series of public concerts, taking music from the spheres of court, church and opera house into the realm of audiences who wished to gather simply for the pleasure of listening. He saw that instrumental music in these other spheres was merely an adjunct to ceremony, contemplation or amusement, and that music could and should be appreciated as an abstract art, unadorned, and not subservient to other goals. His insight revealed a path that composers, performers, and audiences have trod ever since, leading directly to our concert today.

Although Telemann was the most prolific of 18th-century composers (a period when prolific composers abounded), he still found time to travel frequently and widely across Europe, absorbing musical influences from a wide variety of composers and nationalities. The “Concerto Polonois” was a result of a visit to Cracow, Poland, and it incorporates characteristic elements of Polish folk dance and presents them in the new compositional style.