20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Vittorio Giannini (1903-1966) was an influential American composer and teacher in the first half of the 20th century. He served on the composition faculties of the Juilliard School, Manhattan School of Music, the Curtis Institute, and the North Carolina School for the Arts; among his students were many prominent American composers, including John Corigliano, David Amram, and Nicholas Flagello.

A prolific composer in a neo-romantic style, Giannini wrote numerous symphonies, over 12 operas, works for concert band, songs, concertos and chamber works; his most enduring success was an opera buffa adaptation of Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew. His compositional style grew darker and more complex towards the end of his life, and this is reflected in his Psalm 130, a work of anguish and passion – and a tour de force for the double bass.

Giannini composed the Psalm in 1963 when he was in the midst of being divorced from his young wife, and he poured his soul into this piece. The Psalm is in three sections. It opens with a declamatory statement in the high winds and strings, based on a minor seventh, which is the work’s main theme. The middle section is slower, wistful, and somber, with the soulful double bass line set off against plaintive woodwind motifs. The third section returns to and intensifies the opening theme, interspersed with double bass recitatives, before coming to an abrupt and intense end.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

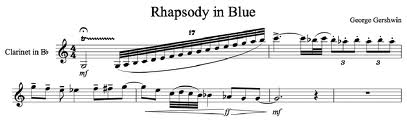

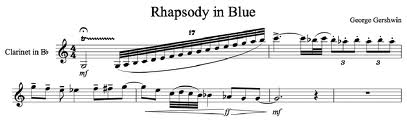

Gershwin composed the Rhapsody in just a few weeks in early 1924. It was orchestrated by Ferde Grofé (of Grand Canyon Suite fame), and premiered in New York, in February 1924, by Paul Whiteman‘s Palais Royal Orchestra band. It had enormous popular success, and instantly catapulted Gershwin to worldwide fame.

This is a quintessentially “American” work – brash, bold and exuberant; a fusion of classical and jazz styles; a piece in which the piano is both featured soloist and very much a part of the whole ensemble.

A long, low clarinet trill and rising “glissando” scale lead into the first triplet-based theme, punctuated by syncopated rhythms in the brass and winds, repeated and developed by other sections of the orchestra and the solo piano, and interspersed by solo piano variations.

Near the middle of the piece, the classic slow “blues theme” makes its appearance in the strings, is amplified by the full orchestra, and develops into the rousing finish.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

A gifted and eclectic composer, Griffes was born in western New York in 1884 and died prematurely in 1920 at the age of 35. Although he studied with German pianists and composers, he was most influenced by early 20th-century French and Russian composers, and by oriental music.

He was also interested in Native American music, incorporating it into his compositions. His Poem is a fantasy for solo flute, 2 horns, harp, strings and percussion, with clear impressionist influences. Its alternating tranquil and rhythmically driven sequences and bold tonalities make it a compelling piece for audiences – and a perennial favorite for flutists.

Romantic, Solo with Orchestra, Works

In Scotland, the cross-fertilization between classical violin music and traditional fiddle tunes began in the 18th century. Because fiddle players in Scotland had an unusually high rate of musical literacy, their folk music, unlike that in other countries, was often learned and written down. As a result, hundreds of printed and manuscript collections were created between the 1740s and the end of the century. Max Bruch found some of these Scottish melodies in a copy of Scottish Musical Museum by James Johnson, during a visit to the Munich Library in 1862. He said that the Scots tunes “pulled me into their magical circle” and that they were more beautiful and original than folk tunes from Germany.

The “Fantasia for the Violin and Orchestra with Harp, freely using Scottish Folk Melodies,” better known as the “Scottish Fantasy,” was written mostly during the winter of 1879–80. Bruch struggled over whether to call the work a fantasy or concerto and in the end chose the word “Fantasy” because of its free style. Unlike a normal fantasy, however, the Scottish Fantasy consists of four full-fledged movements. The role of the harp, an instrument associated with Scotland’s earliest traditional music, is nearly as prominent as that of the violin soloist.

Each of the Scottish Fantasy’s four movements are based on a different Scottish folk tunes. The piece begins in darkness, evoking the image of “an old bard, who contemplates a ruined castle, and laments the glorious times of old.” We then are introduced to the 18th century tune “Through the Wood Laddie.” The second movement is based on “The Dusty Miller,” a lively, cheerful tune that first appeared in the early 1700s. “Through the Wood Laddie” is revisited in the transition to the third movement whose main theme is derived from the 19th century song, “I’m A’ Doun for Lack O’ Johnnie.” The main theme of the finale is the unofficial Scottish national anthem, “Scots, Wha Hae,” (Robert Burns’ tribute to the 1314 Battle of Bannockburn). This ancient war song and “stomping dance” has taken on many different titles and sets of lyrics over the years. Bruch alternates virtuostic variations on the main theme interspersed with a contrasting lyrical melody. After one last appearance of a phrase from “Through the Wood Laddie,” the Scottish Fantasy concludes triumphantly.

Classical, Solo with Orchestra, Works

As part of his vast musical output, Mozart wrote numerous works for use in church services. Among them were 17 short pieces, none more than 4 minutes long, known as “Church Sonatas” or “Epistle Sonatas.” They were meant to be played during Mass, and were composed by Mozart as part of his duties for the Archbishop of Salzburg. These charming works display Mozart’s customary elegance and grace. Most of them are scored for violins, bassi (‘cello, bass and bassoon) and organ. This includes K. 69, which we’re performing today – and which Mozart composed in 1772 when he was just 16 years old.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

“Tubby,” with music by George Kleinsinger and story by Paul Tripp, was composed in 1946. It serves as a wonderful introduction to the orchestra, and has become a well-loved children’s classic.

It tells the story of Tubby, a fat little tuba who just wants to be treated like all of the other instruments of the orchestra. As the lowest-sounding instrument, Tubby usually just gets to play “oompah-oompah.” What he really wants is to play pretty melodies just like all of the other instruments in the orchestra!

When Tubby first tries to do that, the other instruments make fun of him. After rehearsal, Tubby goes home and sits sadly by a riverbank; but there, he meets a big bullfrog, who teaches him a wonderful new melody. At the next rehearsal, the conductor gives Tubby the chance to play his new melody. Tubby plays it so beautifully that all the other instruments love it and want to play it too!

Everyone joins together in the rousing finale, making Tubby a very happy tuba indeed.

Romantic, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Carl Maria von Weber was one of the pioneers, if not the preeminent pioneer, of German Romanticism in music.

The Andante and Rondo Ungarese (Hungarian Rondo) was originally written, in 1809, for viola solo and orchestra. Von Weber later re-worked the piece for bassoon solo (1813), upon request of Georg Friedrich Brandt, bassoonist of the Munich Orchestra. The Andante is a set of short variations. The rondo marks one of the early points of Germanic fascination with things Hungarian in its rollicking melody and dance-like character. Later well-known examples of this fashion are Brahms’ Hungarian Dances and the finale of his violin concerto.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Both Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Ralph Vaughan-Williams were intensely interested in the folk music of their native soil. Each composer attempted to create a distinctive national style by incorporating local folk tunes, rhythms, and harmonies into their art.

The two works that we are to hear today are excellent examples of this process. “The Lark Ascending” draws its inspiration from the mysticism of the English countryside, setting several folk tunes in a quiet manner, conveying a calm, peaceful and transcendent mood to the listener, with the solo violin observing and commenting on the scene from afar. The work begins and ends with meditative reveries from the solo violin.

The “Fantasy on Russian Themes” sets the solo violin in an active mode, with the brilliance and power to compete directly with an exuberant orchestra. Here, too, the violin is given solo moments of an improvisational nature, but rather than the inward-looking ruminations of the “Lark,” we are presented with what are merely lyric interruptions in an otherwise boisterous, robust scene of a country gathering. Here joyous peasants participate in the highly social activities of dancing, singing and drinking among family and friends.

The two works together are an interesting study in contrast, and provide an enchanting view into two artistic minds as they envision a showcase for the solo violin.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Both Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov and Ralph Vaughan-Williams were intensely interested in the folk music of their native soil. Each composer attempted to create a distinctive national style by incorporating local folk tunes, rhythms, and harmonies into their art.

The two works that we are to hear today are excellent examples of this process. “The Lark Ascending” draws its inspiration from the mysticism of the English countryside, setting several folk tunes in a quiet manner, conveying a calm, peaceful and transcendent mood to the listener, with the solo violin observing and commenting on the scene from afar. The work begins and ends with meditative reveries from the solo violin.

The “Fantasy on Russian Themes” sets the solo violin in an active mode, with the brilliance and power to compete directly with an exuberant orchestra. Here, too, the violin is given solo moments of an improvisational nature, but rather than the inward-looking ruminations of the “Lark,” we are presented with what are merely lyric interruptions in an otherwise boisterous, robust scene of a country gathering. Here joyous peasants participate in the highly social activities of dancing, singing and drinking among family and friends.

The two works together are an interesting study in contrast, and provide an enchanting view into two artistic minds as they envision a showcase for the solo violin.

20th Century, Solo with Orchestra, Works

Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992) was one of Argentina’s most gifted and prolific composers. He was a self-taught composer and an accomplished player on the bandoneon, the Argentine version of the accordion. Piazzolla is inextricably associated with the tango, which he was largely responsible for re-energizing and modernizing in his numerous compositions.

In his Histoire du Tango, Piazzolla sought to trace the evolution of the tango itself from an erotic, “not quite respectable” dance to its modern form, which is still very much alive and well in today’s Buenos Aires.

The Histoire is a series of four pieces – “Bordel 1900, Café 1930, Nightclub 1960, and Concert d’aujourd’hui” – which he composed originally for flute and guitar. We are performing the third piece in this series, in an arrangement for soprano saxophone and orchestra by Mark Spede.

Like all tangos, the music is full of wistful melody, with abrupt rhythms alternating with hints of sadness and languor.