Symphony No. 29 in A Major

One of the more frequently performed early symphonies of Mozart.

One of the more frequently performed early symphonies of Mozart.

Mozart wrote this work in 1782 for the ceremonies surrounding the ennoblement of Sigmund Haffner, a member of a prominent Salzburg family. He originally wrote this piece as a six-movement serenade, including an introductory march and two minuets. He wrote it in just a few short weeks in the summer, and there is no record of a performance at that time. However, in December 1782 Mozart decided he wanted to perform it in Vienna in a concert and asked his father for the score.

When he received the score, Mozart was astonished at how good it was, because he had forgotten every note of it! He promptly went about revising the piece for his upcoming performance. He dropped the introductory march and one minuet and organized it into the familiar four-movement symphony we know today. A few years later he added flutes and clarinets to the outer movements.

The symphony’s outer movements are full of brilliant passagework, flair, and dash. Mozart specified that the first movement was to be played “with great fire.” It opens with a famous octave leap upwards, and then downwards, with embellishments — a theme which is repeated throughout. The second movement is a simple (yet subtle) andante, with a relaxed atmosphere. It first features a lyrical violin melody accompanied by a wind chorale; the contrasting second theme is introduced by the 2nd violins and violas. The third movement is a foursquare minuet, with a lyrical counterpoint in the trio. The final presto (according to Mozart, “as fast as possible”) opens with witty understatement, spins out an intimate second theme, and ends with a magnificent triumphal flourish.

— M.F. Tietz

Czech composer Antonin Dvořák was born in a village near Prague. Despite his father’s wishes for him to continue in the family business and become a butcher, Dvořák pursued his career in music and by the age of 18 was working as a fulltime musician. During his childhood he developed a deep passion for his heritage and fell in love with the native folk tunes and bohemian melodies associated with his village. It was these early influences that shaped Dvořák’s style. Much of his repertoire is based on Bohemian folk songs and melodies.

Dvořák moved to New York in 1892, after he was named the Director of the National Conservatory of Music. He lived not far from there, at 327 E. 17th Street, just down the street from where the Conservatory used to be (there is a high school there now). It was there that the “New World” Symphony and the Cello Concerto in B Minor were written. The “New World” was commissioned by the New York Philharmonic and premiered in December of 1893 at Carnegie Hall. Because of his love for folk music, Dvořák was very interested in Native American and spiritual melodies and themes, and said upon his arrival here, “I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America and your composers must turn to them.”

Dvořák said of the “New World” the day before its premiere, “I have not actually used any of the [Native American] melodies. I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of the Indian music and, using these themes as subjects, have developed them with all the resources of modern rhythms, counterpoint, and orchestral color.”

Throughout this piece, the listener can pick out the influence of these themes on the symphony. The main theme in the second movement is perhaps the most famous melody that Dvořák wrote and has been used widely in TV and Film scores. It was played during the coverage of the landing on the moon and subsequent celebrations of that event.

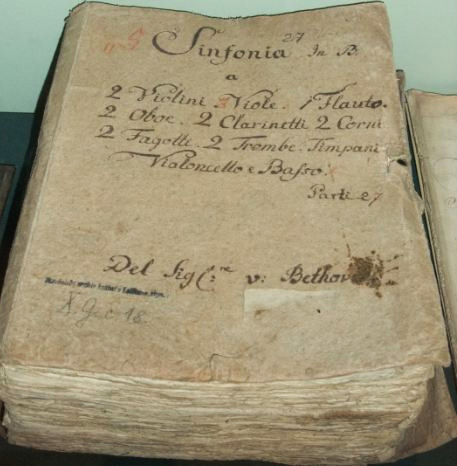

Beethoven composed his Symphony No. 4 in B-flat Major, Op. 60 in the summer and the fall of 1806. 1806 was one of the most productive years of Beethoven’s entire life. During this year, he completed his Piano Concerto No. 4, the Violin Concerto, Leonore Overture No. 3, Coriolan Overture, the Three Rasumovsky String Quartets, the Piano Sonata No. 23 “Apassionata” and the 32 Variations on a Original Theme in C minor.

Beethoven conducted the first private performance of the symphony at the home of Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz in Vienna in 1807, and the first public performance in April 1808, in Vienna’s Burgtheater.

Although not as popular and not as frequently performed as the Third and the Fifth, the Fourth Symphony has a unique place in Beethoven’s catalogue. Today’s audiences, perhaps swept away by the works’ tragic and heroic power, tend to prefer the odd-numbered symphonies. However, Beethoven’s even-numbered symphonies show equally profound and beautiful aspects of his genius. In a critical study of Beethoven’s symphonies, Berlioz said of the Fourth Symphony: “The general character of this score is either lively, alert and gay or of a celestial sweetness.” Robert Schumann compared the work to “a slender Grecian maiden between two Nordic giants,” having in mind the sequence of the Third, Fourth and the Fifth symphonies.

The first movement of the Fourth Symphony opens with a slow introduction (Adagio) in which we have the feeling that the time is standing still. The cold and motionless music from the introduction is “detonated” by the flamboyant chords of the sonata allegro (Allegro vivace) giving energy to a joyous and Haydnesque movement almost entirely based on the opening staccato notes of the first theme.

The second movement (Adagio) brought Berlioz to exaltation — “Its form is so pure and the expression of its melody so angelic and of such irresistible tenderness that the prodigious art by which this perfection is attained disappears completely.”

The third movement (another Allegro vivace) is based on the constant juxtaposition between duple and triple pulse. The entire movement is repeated twice, thus becoming a model for Beethoven’s Fifth and Seventh symphonies.

The fourth movement (Allegro ma non troppo) returns to the sparkling and playful mood of the first movement. Here sudden dynamic contrasts and furious passages in sixteenths become the moving forces. At the end of the movement, Beethoven again pays homage to his teacher Haydn by lulling the listener to repose before the final outburst.

The Ninth Symphony is emblematic of the high-wire act required of a Soviet composer under Communist rule. Shostakovich’s transcendent musical gifts won him status as the Soviet Union’s leading composer, a stint as the president of the composers’ union, and international acclaim, despite two periods when he was out of favor with officialdom at home. As a young man, he ardently embraced socialist ideals, but later, after successfully responding to political criticism from the state with his Fifth Symphony, he tried to remain above the political fray. Even when he was out of favor with the Communist regime, he was never dispatched to the gulags. He remained an economically favored hero of the Republic with a country dacha and an active social life with his musical colleagues. In public, he never criticized Stalin or the Soviet government, but in private life he mocked the bureaucracy and its heavy-handed interventions in the creative process. As a result, a sarcastic tone permeates the Ninth Symphony.

Composed near the end of World War II in honor of the military victory in Europe (VE Day—May 8, 1945), Shostakovich adopted a surprisingly transparent neo-classical approach supplemented with a bombastic sneer. Reputedly, he was inspired by playing piano four-hand reductions of Haydn symphonies on a nightly basis with his friend and fellow Soviet composer Dmitri Kabalevsky. Yet Haydn never used low brass and percussion the way Shostakovich does in the Ninth. That enables the Russian to infuse his symphony with a frantic, 20th-century edge that many have interpreted as subversive. Although initially well received, the symphony was banned in his home country in 1948 and not reprieved until 1955.

The Ninth Symphony is divided into five movements. The first, an Allegro in sonata form, is crisp and bouncy, with the upper parts classical. A snare drum adds a brisk military air, and the trombones add some insistent bombast. But even the very neo-classical upper parts, chock full of short, precise notes, are skewed with a scattering of extra beats, giving the rhythm a scrambled, off-balance feel. The Moderato movement opens with a plaintive clarinet solo, later taken up by the flute. It is very Russian sounding. Tension builds as the strings take up a slightly drunken-sounding ascending scale theme. The lonely flute and clarinet return with pizzicato string accompaniment, the theme is passed to the trombone, and the strings let out a descending sigh.

The Presto reprieves the rising and falling scales but against a very different them—evoking a bouncy, balletic tip-toeing with racing clarinet and piccolo. A heroic trumpet solo blasts through. The movement is followed immediately by a Largo, introduced by a melodramatic brass chorale, giving way to a mournful bassoon solo, which some identify as a Jewish theme, perhaps in protest of Stalin’s pogroms. The movement comes to a false cadence, then transitions into the Allegretto, starting with a playful bassoon romp, then building into a triumphal, mad rush to the end.

Notes by Emily S. Plishner

César Franck was 66 when he completed the Symphony in D minor, his only symphony.

It premiered the next year, on February 17, 1889, nine months before the composer’s death. Performed by the orchestra of the Paris Conservatory under the direction of Vincent d’Indy, it was a complete catastrophe. Only now, more than 130 years later, can we see that the features which caused the negative turmoil at the premiere are precisely what cause our admiration today: the symphony’s then atypical three-movement structure, its extremely dense (at times almost Wagnerian) texture, and its organ-like overall sound.

The symphony is in three movements with the first having probably the most peculiar structure of the three. It is a richly modified sonata movement in which, not the themes, but the two tempos (Lento and Allegro non troppo) define the development. The heavy and dark introduction sets the main question of the symphony and a quick answer follows at the beginning of the Allegro. The symphony’s first surprise occurs when, in the middle of the allegro exposition, Franck returns us to the very beginning of the story by reintroducing the entire introduction, this time not in D minor, but in F minor. A second Allegro non troppo takes over leading us successfully out of the darkness. The final appearance of the Lento at the very end of the first movement brings a bright apotheosis.

The second movement is a unique hybrid of an old ballad and a scherzo that is directly derived from the ballad material. The scherzo starts as a harmless tremolo in the strings and grows monumentally toward the end of the movement. The expressive solo of the English horn at the very beginning of the movement was only one of the specific reasons for the conservative audience of Paris rejecting the work — in those days an English horn solo would be expected in an opera but not in a symphony.

The third movement begins with a stormy tremolo in the strings that is quickly interrupted by five short and powerful chords leading us to a movement that is simply a triumph of thematic richness and formal fantasy. This is also the movement in which the global plan of the symphony is revealed to us in the form of the reappearing ballad, but now heroic and with full-pipe organ volume.

Schubert composed his Symphony No. 8 (“Unfinished”) in 1822 and kept it a deep secret for the rest of his life. Even after the composer’s death in 1828, the premiere of the symphony had to wait an additional 37 years until 1865 when it was performed in Vienna under the direction of Johann Herbeck.

The two-movement structure of the “Unfinished” Symphony has raised many questions and debates during the past 150 years. All resulting theories and assumptions have their strong and weak points. Some of today’s theorists have concluded that Schubert in fact completed the work by writing what is known today as the First entr’acte of the incidental music to “Rosamunde”. This theory is based on the fact that both symphony and entr’acte are in the key of B minor, a fairly rare key for a symphony even in the beginning of the nineteenth century. A second argument supporting the ‘Rosamunde’ theory is that at the time he composed the symphony, Schubert had to complete, in a very short time, some incidental music. According to the theory, Schubert sacrificed the finale of his symphony in order to secure his income.

A second theory as to why the composer did not write a third and fourth movement for his most famous instrumental work is based on a very simple and purely aesthetic observation: these two movements say everything the composer had to say. In his book Schubert: A Musical Portrait, Alfred Einstein argues that “He [Schubert] had already written too much that was “finished,” to be able to content himself with anything less or with anything more trivial.”

The first movement begins with an introduction, based on an 8-measure motive, which although not having the status of an independent theme, plays a significant role in the unfolding of the first movement. The themes of the sonata allegro are of a rich singing quality and each complements rather than contrasts with the other. This is a movement in which the romantic intensity is masterfully mixed with tender lyricism. The movement ends in darkness and pessimism: the opening motive is broken to short segments without gravity and without hope.

After the intensity and the dramatic force of the first movement, the second movement presents even more imaginative compositional and melodic structure. Here we have virtually everything the listener can desire to hear in a romantic work – almost “lied”-quality melodies, heroic frescoes, explosive climaxes, and sudden harmonic shifts.

Composed between 1800 and 1803, this work can be viewed as both the culmination of the first phase of Beethoven’s orchestral writing and as a major advance towards the work of his “heroic” period.

While outwardly classical in style, this symphony is full of drama, contrast and lyricism. It begins in a grand style, with an opening Adagio based on rising and falling scale motifs. The opening section segues into a sparkling Allegro con brio starting in the lower strings, with dramatic drive and dynamic contrasts.

The lovely theme of the second movement Larghetto is one of the most recognizable passages in classical music – a lyrical rising melody played first by the strings in a high register, and then echoed by the winds. A short development section uses the opening theme as a backdrop to evoke an unsettled and then stormy mood before returning to the opening’s calm lyricism.

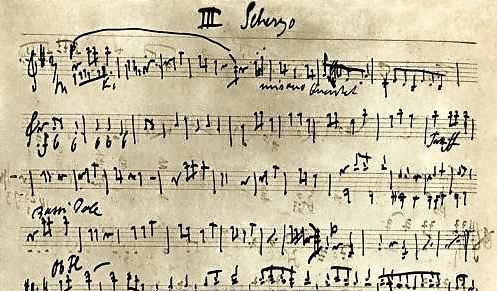

The joyous Scherzo has sudden dynamic contrasts and a lovely Trio featuring the winds.

The symphony concludes with a brilliant Allegro molto, which is based on a fiery short opening string motif and punctuated with a dramatic stop. Rich harmonic improvisation and use of the opening motif characterize this movement, which ends with a triumphant flourish.

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) composed his “Spring” symphony – his first major orchestral work – when he was 31. He wrote it at a happy time in his life, shortly after his marriage to the former Clara Wieck, who encouraged him to pursue orchestral composition.

Schumann was initially inspired to write the symphony by a poem describing “springtime” (he initially even put names to the movements, before removing them so as not to have the work appear to be programmatic). But the “Spring” appellation stuck, and the work displays an appropriate heady optimism and beauty. Schumann sketched it in a mere four days, and it was premiered in March 1841 in Leipzig by Felix Mendelssohn.

The symphony is in four movements. The opening Andante is heralded by a horn and trumpet call (“like a summons to awakening”), which becomes the basis for the sprightly theme which follows. The second movement is a dreamy larghetto (initially titled “evening”), with a lyrical theme repeated by violins, ‘cellos, and solo oboe and horn.

A passage in the trombones serves as a bridge to the unique third movement, a fast scherzo with 2 delightful contrasting trios.

The fourth movement is based on a graceful and witty theme begun by the violins, with subtle counterthemes in the winds. An intense accelerando leads to a triumphant climax.

Although a quintessentially French composer, Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) composed his third symphony on a commission from the Royal Philharmonic Society in England, and conducted the première himself in London in 1886. Popularly called the “organ” symphony, it is actually a symphonic work which features an organ in two of its movements (with notable effect). Saint-Saëns wrote this as a two-movement work, although it has the feel of a four-movement piece. It has an unusual and large instrumental complement (besides the organ, the second movement has 2-hand and 4-hand piano parts).

The 3rd symphony is a masterpiece of composition, with most of the thematic material developed from the opening parts of the first movement. A slow introduction features rising lines from the oboe and flutes, which are then prominently featured throughout the first movement. The following allegro features a fast off-the-beat string theme in C minor, echoed by the winds. Saint-Saëns uses this theme throughout the symphony in various guises – such as pizzicato figures in the low strings, melodic solos in the woodwinds, and last (but not least!) in the second movement.

The adagio at the end of the first movement introduces the organ as both accompaniment and obbligato to an ethereally beautiful rising string melody, which is repeated by wind soloists (clarinet, horn and trombone), with subsequent variations by the violins and full orchestra.

The second movement begins with a repeated vigorous triple meter allegro, and an even faster presto section (reminiscent of classical minuet and trio movements); the presto features wind flourishes brilliant piano scales. After a soft choral interlude in the strings, the organ makes its grand entrance; the first movement C minor string theme majestically reappears in C Major (first in the strings and 4-hand piano, and then in the organ and brass).

A vigorous fugal section gives way to ever faster variations on the main themes. After a descending scale in the organ, the symphony ends in a rousing flourish of trumpets, brass and timpani.