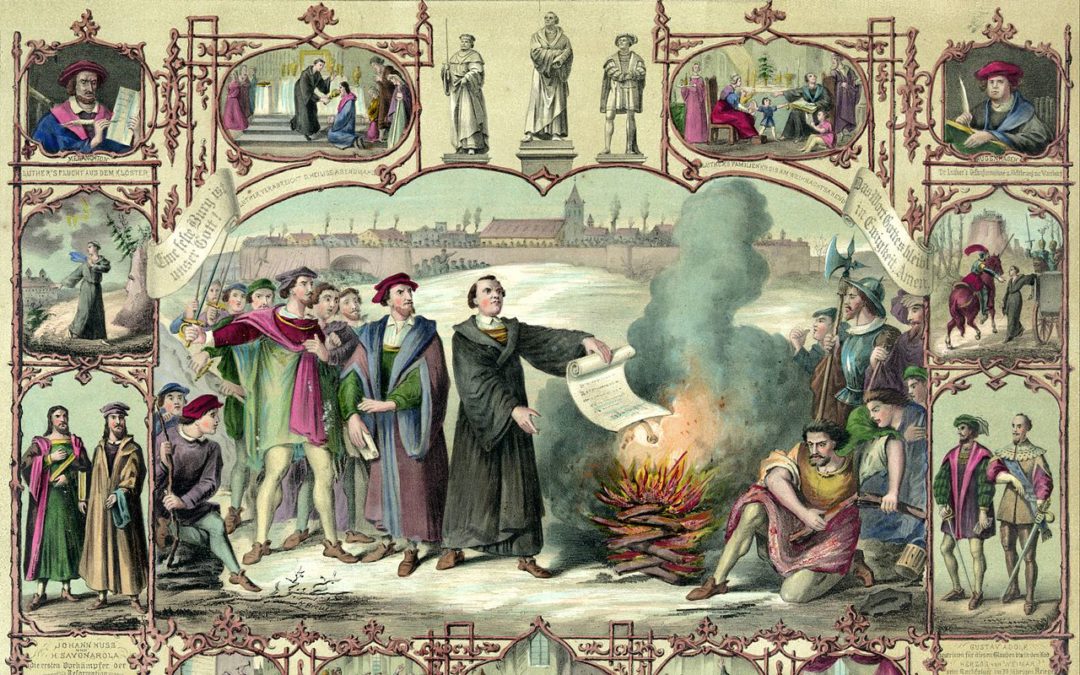

The “Reformation” is one of Mendelssohn’s most programmatic works. As befits its title, the symphony’s first and last movements each contain elements of religious struggle and triumph. Though catalogued as Mendelssohn’s fifth symphony, it is actually his second “full” symphony, written in 1829-30, just three years after Beethoven’s death.

He originally composed his “church symphony” to be played at the 300th anniversary of the Augsburg Confession of 1530 (which defined the doctrines of the Lutheran Church). For various reasons, however, his new symphony was not chosen for that occasion. Mendelssohn then sought out other venues for it to be performed, and it was eventually performed in Berlin and played at a rehearsal in Paris. Unfortunately, it was not favorably received by critics or musicians, even after Mendelssohn made revisions to it in 1832. He finally “shelved” the symphony for the remainder of his life, refusing to let others see it, and even contemplated destroying it. The symphony was finally published in 1868, over 20 years after his untimely death. Since four other Mendelssohn symphonies had already been published, this one was presented as his “Fifth” Symphony. Since then, it has made its way into the standard symphonic repertoire, albeit in Mendelssohn’s “revised” 1832 version. The version we’re performing today is the original 1829 version, which notably includes a rarely-performed Recitative movement before the Finale.

While written in Mendelssohn’s unique style, the “Reformation” contains references to other composers, including Mozart (opening theme based on four-note “Jupiter Symphony” theme); Bach (fugal and counterpoint sections in the fourth movement); and most interestingly, Beethoven – in the choice of key (D minor/Major), the use of a recitative before the last movement, and a last movement based on a hymn or song (all possibly hearkening back to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony).

The first movement opens in an “antique” polyphonic style reminiscent of Catholic Church ceremony, interrupted increasingly by strident brasses and woodwinds (possibly showing the Catholic order being challenged by the new Protestant movement). At the end of the opening Andante, Mendelssohn has the strings softly playing the “Dresden Amen” — a rising six-note theme. The fiery Allegro which follows is full of musical struggle and combat, with violent string passages met with wind outbursts based on a two-note theme (also derived from the “Dresden Amen”).

Andante – Allegro con fuoco

The second movement is a carefree scherzo, with a singing trio section featuring oboes and strings.

Allegro Vivace

The intense third movement is an orchestral “song without words” featuring strings, oboes and bassoons, in turns introspective and impassioned.

Andante

The Recitative, prominently featuring a solo flute and wind choirs, follows without a break. It leads directly into the choral finale based on the Lutheran hymn “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” (A mighty fortress is our God). The opening chorale is introduced by solo flute and woodwind choir. Mendelssohn develops the movement into increasingly faster variations, complete with Bachian counterpoint in the strings. He overlays passages from the chorale in the middle of the movement, and uses it again in the coda as an exclamation point to end the symphony in dramatic fashion.

Andante con moto – Allegro vivace – Allegro maestoso

Symphony No. 5 in D Major

Op. 107, "Reformation"

Composed in 1830

By Felix Mendelssohn